When I went to the Viable Paradise writer’s workshop back in the distant dim year of 2013, the inestimable Elizabeth Bear, along with various other people who are cleverer than me, explained to me about the tricks a writer gets for free in their box. The writing-skill cards you drew in your first poker hand.

The magic of this idea is that it is a promise: everyone gets something. Every writer, no matter how green, has at least one thing they’re good at to start off with. It could be character, or prose rhythm, or pacing. Or the instructions to the Plot Machine. (The people who got the instructions to the Plot Machine are very lucky, and I hate them all with a profound envy. My Plot Machine instructions were incomplete and mostly made of those guys from the IKEA instruction manuals, gesticulating happily at a pile of incomprehensible parts.)

Your One Free Trick is the skill you can build on. The skill you can lean on, while you learn the rest of the craft of being a writer. Thinking about writing craft in this way—as a collection of interlinked skills, some of which you got for free, some of which you have to work for—completely changed how I approached new and hard projects. In a certain sense, this concept let me learn how to write a novel.

Novels are, for those of you who were not aware, really damn hard to write. Especially if you were, like me, a person who had been merrily writing short stories with some success for a good while before taking the plunge into longform narrative. Novels are hard for a lot of reasons—David Hartwell said that “a novel is a work of fiction longer than a short story, and flawed”, or at least that’s what I’ve heard that he said—but for me, the most difficult part of writing one was that there were so many words in it. (Hear me out.) A novel is very long. The pacing of it is completely different than a short story. You can write a thousand words, or two thousand words, and still have so much farther to go that all that work is but a drop in a vast and merciless ocean. When I started seriously writing A Memory Called Empire, I didn’t even feel like I was making a great leap into the unknown of a new format: it was more like a slow trudge into the unknown, with every step requiring an individual act of self-propellment. I had to figure out a new way of thinking about writing, one which didn’t make me feel so stuck, so bogged down, while I learned a skill I didn’t have—the skill of writing a piece of fiction longer than a short story.

I started thinking of writing as a practice, the way language-learning is a practice, or yoga, or rock-climbing. Something done consistently over time, that becomes a sequential and evolving exploration. Because clearly I was working on how to write a novel. That’s the part of my practice which I’m actively trying to push into, to stretch myself at. And I remembered the One Free Trick promise: there were skills I got for free, and skills I had to learn. And if I leaned on the skills I had for free, I could help myself while I was learning a new skill.

For my sins, my One Free Trick is setting.

Setting isn’t the worst Free Trick to have as a SFF writer, mind you. You want your weird shit evocatively and coherently described? I have got acres of weird shit to sell you: here is a city made of salt, here is a tongueless and eyeless angel in the form of a sandwich kiosk operator, here is the first Crusade outside of Acre, would you like a free sample of a spaceship which uses corrosive high-surface-tension acids as a zero-gravity weapon? And from setting I fairly quickly picked up theme—the ‘what is this story about’ trick. (For me, since these were the first two skills I had mastery of, they’re intimately linked: the way the setting works conveys the metaphor-set, prose register, and imagery which reinforce the theme, and also delimit the possible ‘what is this about’ questions to a narrower set). Of course, this meant that most of my early work is evocative-yet-overdescribed symbolic worldbuilding. (I got better.) Over several years of writing short fiction and fanfiction, I picked up a halfway decent set of prose and character tools by dint of practice.

But none of that was going to get me through Writing A Novel—the pacing challenges, the stamina challenges, the plot challenges. So many things happen in a novel. One after the other. All these events. And they all have to be the right events to move the story towards the thematically-appropriate ending, which, oogh. So hard. Even though I subscribe to the ‘plot = character + situation + problem’ rubric, I often find that despite having Situation and Character to start with, and enough determination to chew on those both until I discover a Problem, which will give me the thematic question of the piece and some ideas for the end … but it’s awfully hard for me to turn a Problem into events-in-sequence. And you sure need those for a novel.

Buy the Book

A Memory Called Empire

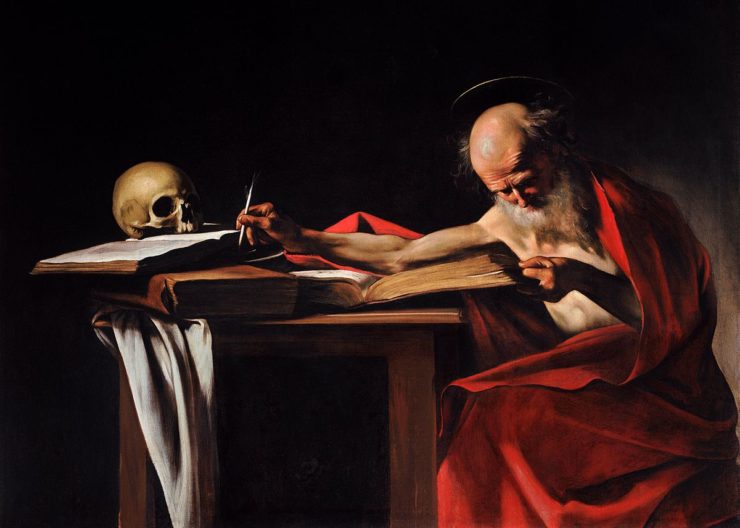

So I went back to my Free Tricks. How could I use setting and theme to push me through while I worked on learning the skill of novel? First, I made some slightly conservative—conservative in the sense of not taking risks—choices about what kind of novel I was going to write. For instance, I decided to work in cultural context I feel very capable of and comfortable writing (inspired by middle-period Byzantine literati culture—just IN SPACE!) with character types I know I can write well (poet-diplomats are a specialty) and thematic concerns that I find deeply energizing and pleasurable to explore (memory preservation, imperialism and the colonized mind, uniqueness of individual identity).

I let myself pick things to put in this book that aren’t hard for me, that make good use of my strengths. There’s a ton of lush visual description in this book—buildings and clothing and peculiar food items, everything having enormous symbolic weight … because I love that stuff, and because I’m good at it. And then I turned those lush visuals into weight-bearing parts of the book—plot-bearing parts of the book. I’ve even used my One Free Trick skills to get unstuck on transitions or scenes I’d paused on for a while: I’d describe, in detail and with precision, one of those important symbolic visual setting elements, but I’d do it from my POV character’s impressions and understanding of what she was seeing. Eventually I would see why my protagonist would be looking so closely at that thing—and I’d be in the scene, deep in the character’s voice, and I’d have done some thematic work to keep the story moving along.

Your One Free Trick might be very different from mine. But the principle is the same: if you’ve got character, use your characters to drive your plot and your setting. If you’ve got structure and pacing, build yourself a scaffold of an interesting structure to hang your character work on. (I think the Structure People must outline a lot. The Structure People are cool.) Your One Free Trick is your fallback position. It’s what you can use to propel you through the long, difficult process of learning something new—of working on drawing the cards you weren’t dealt in your initial Writing Skill hand. Of treating writing as a practice.

Arkady Martine writes speculative fiction when she isn’t writing Byzantine history. She is overly fond of borders, rhetoric, and liminal spaces. Her novel A Memory Called Empire publishes March 26th with Tor Books. Find her on Twitter as @ArkadyMartine.

“Learn this one weird trick that writers hate!”

;)

Sometimes it’s really hard to even know what your one free trick is.

I used to think mine was world-building and maybe it is, but the tedium of describing it is a pain. Then I, quite accidentally, discovered I love writing dialogue. I think (though I may be deluding myself) that I’m pretty good at it. Certainly better than describing things or this “plot” that everyone keeps talking about.

When I finished my first novel (totally unpublished), it’s mostly people talking. Usually in a snarky, humorous, slightly offensive manner.

What’s funny though, is those are the books I want to write. I want to be Tom Clancy or David Weber, but I’m obviously not. Now to figure how to follow through with this for a novel that people might want to read.

Like you, I am filled with enmity for those people who got the Plot Machine instructions, and also the Structure People, except fortunately we know some of them and can get help.

I got Characters. Which isn’t bad, but it made plotting the books hell. On the other hand, it makes picking up and writing on a day when I’d rather do almost anything else much easier than it could be.

Anyway, I’m really looking forward to A Memory Called Empire.

Thanks for this. It made me think about my strengths and weaknesses.

I got Dialogue. I can write the hell out of a couple of people talking in a coffee shop – or a tavern, when I’m working in Fantasy – but how that dialogue will relate to the plot? Enh. And forget about Setting. I’m absolutely envious of anyone who gets Setting as their skill, because I can’t describe that coffee shop or tavern to save my life. Oh, look. There’s a chair. And, um, there are windows. Everything’s brown, y’all. Lot’s of, you know, wood.

It’s worrisome, but on the other hand… Aaron Sorkin. That dude made a career out of getting Dialogue as his One Free Trick. So I’m not hopeless.

I got Structure with a side order of theme, but I’m a playwright. All my friends got Dialogue and Character. :(

And, this, boys and girls, is why writing courses are a very, very good thing because a good teacher can help you pull all those weak skills together with that strong skill to make a novel.

You had me at “Byzantine literati” and clinched it with “poet-diplomat;” definitely going to get my hands on this one. (My tastes, they are predictable ones.)

I write for pleasure and enjoyment, not professionally; I think my “free skill” might come down to characterization and its influence on narrative register and the well-chosen character-revealing descriptive detail. (I think I need a Plot Machine to help roll out the rest of it for me like so much pasta dough; do they sell those at Sharper Image, or….?)

Really interesting post!

I think I got humor and Big Ideas.

“…would you like a free sample of a spaceship which uses corrosive high-surface-tension acids as a zero-gravity weapon? “

Had to go research…came away enlightened, but disappointed. Still, like the idea of it, though.

I got humor. I can’t write anything until I come up with a joke. Once I’ve come up with a few jokes, I work to turn them into a story.

http://www.chromeoxide.com/writer/

Possibly I’ve been reading too many game design articles today, because the first thing that pops into my head after reading your post is ‘Novelist: The Deck-building Game’. We all start with one good card and try to gradually accumulate others while discarding bad habits and misconceptions. Might be a useful metaphor (to me, not necessarily anyone else) so thanks for sharing!

No. 12, I can relate. The first thing I thought of was novel writing as RPG. I got a 18 on Dialogue and 17 on Setting, but my Plotting skill is a lowly 6! Now, if only I could find a friendly rogue ninja with high plotting skills we could team up!

To my shame, my first thought was not of self-improvement and honing my skill set, but that if we can get enough of those ‘crippled’ writers, we cam form one true novelist. The one that is the instant classic material, you know? Like Voltron, but with novels.

@12 “Novelist: The Deckbuilding game” is the perfect metaphor to me. (And someone needs to make that game – I’d buy it!).

@14 That’s genius! One of those novelists would have to be the “black lion” though – the one whose skill is bringing together the skills of all the others and making them work as a cohesive whole…

I got Sneaky Worldbuilding (also not a bad draw for SFF) and Perfect Grammar. The latter isn’t as great as it sounds when you’re trying to draft fast, but it’s a really useful skill to barter. I know someone who got the Plot Machine instructions, and her output is prodigious. I’d hate her if she weren’t on my side. ;) I worked hard to level up on Structure because I drew “endless meandering plotter.” :-\

Thanks for this great encouragement/reminder!